Acute Ataxia in Children (Diagnosis)

Neurological, Pediatrics

First 5 Minutes

Important to establish the timeline and evolution symptoms. Hyperacute onset could indicate a life-threatening vascular event.

Red flags: (1,6)

- Altered mental status

- Papilledema

- Nuchal rigidity

- Headache

- Opsoclonus (“dancing eyes”) myoclonus (“dancing legs”) syndrome

- Seizures

- Severe irritability

- Focal neurological deficits (motor, sensation, or reflexes)

- History or signs of trauma

Context

- Definition and DDx (1,2,5)

- Trouble performing smooth, coordinated movements.

- Wide-based “drunken” gait; unsteady upper limb movements; or, often, refusal to walk.

- Cerebellar or motor ataxia → cerebellar deficits.

- Sensory ataxia → proprioceptive deficits (i.e., extra-cerebellar deficits).

- Most cases are self-limited but significant proportion (up to one third) can be

life-threatening. (5)

- Common causes

- Acute cerebellar ataxia (most common).

- Toxic ingestions, medication induced.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).

- Migraine or vertigo related.

- Can’t miss causes

- Tumors.

- Intracranial bleed.

- Vascular (stroke, vertebral artery dissection.)

- CNS infections.

- Autoimmune processes (e.g., acute demyelinating encephalomyelities, ADEM).

- Trauma.

- Other causes

- Metabolic.

- Congenital.

Diagnostic Process

- History (1,2,5,7,8)

- What’s the symptom timeline and evolution of symptoms (acute <7d vs. subacute vs.

chronic/episodic?) - Has this happened before?

- Possibility of toxic ingestion?

- Recent infections (e.g., varicella, adenovirus, herpes)?

- Change in mental status? 🚩

- Recent irritability? 🚩

- History of seizures? 🚩

- History of trauma? 🚩

- Has this occurred in siblings, parents?

- Associated symptoms

- Any pain or headache?

- Any changes in vision, hearing, gait, coordination, balance?

- Any symptoms of elevated ICP symptoms (headache, n/v, limb weakness or sensory

deficits). 🚩 - Complete medication, OTC, supplement history.

- Past and current medical history.

- What’s the symptom timeline and evolution of symptoms (acute <7d vs. subacute vs.

- Physical exam (1,2,4,5,6)

- Ensure physical exam is age-appropriate. Pay special attention to coordinated movements.

- General Exam Findings and Potential Cause (1)

- Fever → infection

- Abnormal respirations or pulse 🚩 → increased ICP

- Head tilt 🚩→ posterior fossa tumor

- Bulging anterior fontanelle 🚩→ increased ICP

- Opsoclonus and/or myoclonus 🚩→ opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome

(neuroblastoma?) - Otitis media with vomiting, vertigo 🚩→ labyrinthitis

- Meningismus (headache, nuchal rigidity, photophobia) 🚩

- Tick bites

- Rash from prior infection → acute cerebellar ataxia

- Neurological Exam (*essential)

- Gait* – Wide-based? Unsteady? Refusal to walk

- Speech changes

- Eye movements – Nystagmus?

- Coordination*

- Finger nose test

- Rapid alternating hand movements

- Heel tapping

- Heel/shin trace

- Hold full glass of water without spilling

- Proprioceptive testing, e.g., Romberg test (non-cerebellar ataxia)

- Mental status

- Normal MSE → post infectious acute cerebellar ataxia

- Abnormal MSE 🚩→ ingestion, autoimmune (e.g., ADEM), stroke

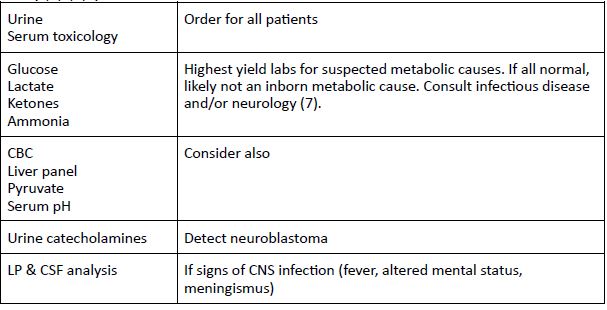

- Labs (1,2,4,5,7)

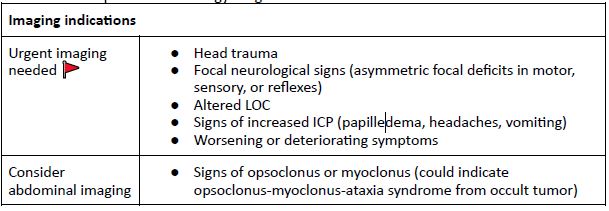

- Imaging (1-3,5,7)

- Not all children with acute ataxia need imaging in ED. Many etiologies are imaging

negative (e.g., acute cerebellar ataxia). - MR ideal (and better for posterior fossa tumors) but CT allowable to rule out surgical

emergencies. - Refer to pediatric neurology for guidance.

- Not all children with acute ataxia need imaging in ED. Many etiologies are imaging

Recommended Treatment

Management (1,2)

- Treatment depends on etiology.

- Symptomatic and supportive care for most patients.

- Refer for treatment of non-acute causes.

Criteria For Hospital Admission

- Admit with patients with any red flag symptoms 🚩:

- Altered mental status

- Papilledema

- Nuchal rigidity

- Headache

- Opsoclonus (“dancing eyes”) myoclonus (“dancing legs”) syndrome

- Seizures

- Severe irritability

- Focal neurological deficits (motor, sensation, or reflexes)

- History or Signs of trauma

- Admit and order EEG for any patient with seizures, altered mental status, or

fluctuating symptoms. (7) - Admit and consult infectious disease and/or neurology on persistent. (7)

Criteria For Transfer To Another Facility

Base transport decisions on resources available at current center, acuity of presenting illness, and need for intensive interventions (e.g., pediatric neurosurgery).

Criteria For Close Observation And/or Consult

- Outpatients with acute ataxia should be monitored by primary care. Any new focal neurological changes or development of red flag symptoms (see above) may warrant neuroimaging. (1,7)

- Episodic or chronically progressing ataxia warrant referral to pediatric neurology. Conditions of this nature include (1)

- Episodic

- Migraine

- Seizure

- Benign paroxysmal vertigo

- Inborn errors of metabolism (e.g., amino acid, organic acids, mitochondrial irregularities)

- Chronic

- Degenerative disorders

- Inborn errors of metabolism

- Genetic disorders (spinocerebellar ataxias, SCA)

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Episodic

Criteria For Safe Discharge Home

- Considerations for discharge

- Child is stable, not deteriorating.

- Ruled out dangerous etiology with history, physical, labs, neuroimaging.

- Diagnosis identified and/or patient has minimal risk of acutely worsening.

- For post-infectious acute cerebellar ataxia (most common cause) most children completely

recover in 2-4 w. (7)

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Due to variable presentation, etiologies, and quality of evidence. No established guidelines for admission or discharge criteria.

Related Information

Reference List

Agrawal D. Approach to the child with acute ataxia [Internet]. Teach S, Nordli D, editors. UpToDate; 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-child-with-acute-ataxia?search

=cerebellitis&topicRef=6206&source=see_linkGilbert D. Acute cerebellar ataxia in children [Internet]. Patterson M, Teach S, editors. UpToDate; 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 5]. Available from:

Radhakrishnan R, Shea LA, Pruthi S, Silvera VM, Bosemani T, Desai NK, Gilbert DL, Glenn OA, Guimaraes CV, Ho ML, Lam HS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Ataxia-Child. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2022 Nov 1;19(11):S240-55.

Rare Disease Video – Opsoclonus Myoclonus Syndrome – National Organization for Rare Disorders [Internet]. rarediseases.org. [cited 2024 Jan 8]. Available from:

https://rarediseases.org/videos/opsoclonus-myoclonus-syndrome/

Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine – Concepts and Clinical Practice. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

Garone G, Reale A, Vanacore N, Parisi P, Bondone C, Suppiej A, Brisca G, Calistri L, Cordelli DM, Savasta S, Grosso S. Acute ataxia in paediatric emergency departments: a multicentre Italian study. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2019 Aug 1;104(8):768-74.

Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020.

Shakkottai V. Assessment of Ataxia [Internet]. Klockgether T, Perlman S, editors. BMJ Best Practice. BMJ; 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from:

https://bestpractice-bmj-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/topics/en-gb/1097

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Feb 14, 2024

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.