Ascites

Gastrointestinal

First 5 Minutes

- Several life-threatening conditions are associated with ascites:

- Fever or chills/rigours (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, SBP)

- Dyspnea (pleural effusion)

- Hematemesis or melena (variceal bleeds)

- Confusion, disorientation, diurnal changes or asterixis (hepatic encephalopathy)

Context

- Liver cirrhosis is the cause of up to 80% of ascites cases.

- Others include:

- malignancy (10%),

- heart failure (3%),

- tuberculosis (2%), and

- dialysis (1%).

- Up to 25% will develop SBP, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 20%.

Diagnostic Process

- Ascites

- The sensitivity/specificity of physical exam to detect ascites is highly variable.

- In significant ascites cases (≥1.5L of fluid), shifting dullness can achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 83% and 56%, respectively.

- Imaging (U/S or CT) confirmation is required in cases of less ascitic fluid (< 1.5L), obese patients and when undergoing paracentesis.

- U/S

- U/S is recommended as a first-line tool in the diagnosis/triage of ascites.

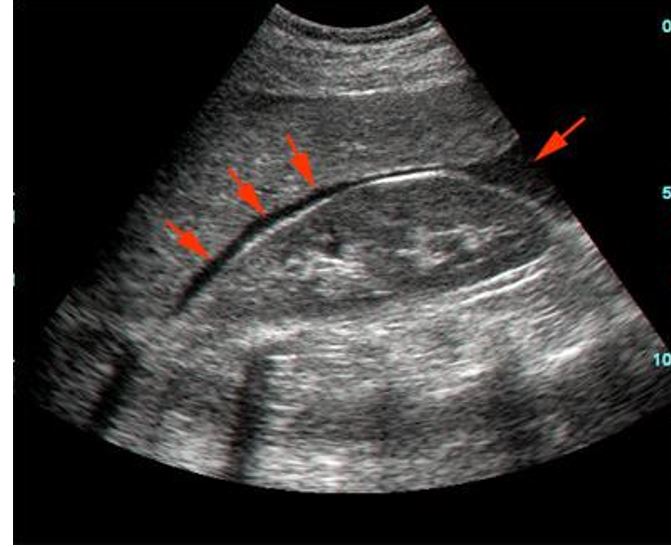

- Scan the patient’s flanks in the mid-axillary line (Morrison’s pouch) and the lower abdominal quadrants (paracolic gutters).

- There may be a role for U/S in differentiating the transudative/exudative nature of ascitic fluid. Transudates are more often anechoic, whereas floating debris and septations suggest an exudative (or hemorrhagic or neoplastic) cause.

Morrison’s pouch with free fluid. From: https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Morison%27s_pouch

- CT

- A small prospective study showed a 75% and 100% sensitivity for identifying free abdominal fluid via U/S and CT, respectively.

- CT may be particularly helpful in situations where abdominal fat occludes U/S or malignancy is suspected.

Diagnostic Paracentesis (Ascitic Fluid Analysis)

Paracentesis can be both diagnostic and therapeutic in patients with ascites and should be pursued in all patients with new-onset and/or unexplained ascites.

- Ascitic Fluid Analysis Markers

- Cell count and differential (PMN cell counts > 250 / mm3 suggests SBP)

- Bacterial culture (if SBP suspected)

- LDH (may be elevated in malignancy)

- Glucose (decreased in infection)

- Amylase (increased in pancreatitis)

- Tumour markers (if malignancy suspected)

- Cytology (if malignancy suspected)

- Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

- Up to 50-75% of patients with SBP will present with fever.

- SBP is diagnosed if polymorphonuclear cell counts exceed 250 cells / mm3 in ascitic fluid.

- Do not delay antibiotic treatment while awaiting culture results.

- For more information: https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/spontaneous-bacterial-peritonitis/

- Pleural Effusion

- Pleural effusion should be suspected in ascitic patients presenting with dyspnea, cough or pleuritic chest pain.

- For more information: https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/pleural-effusion/

- Variceal Bleeding

- Variceal bleeding should be suspected in ascitic patients presenting with hematemesis or melena

- For more information, visit: https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/upper-gastrointestinal-bleeds-in-patients-with-cirrhosis/

- Hepatic Encephalopathy

- Hepatic encephalopathy should be suspected in ascitic patients presenting with any cognitive dysfunction.

- For more information: https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/hepatic-encephalopathy-diagnosis-management/

Recommended Treatment

- Treat underlying cause of ascites if possible.

- The goal is to minimize ascitic fluid without depleting intravascular volume.

- Sodium reduction and diuretics form the backbone of ascites management.

- Therapeutic paracentesis may be performed in symptomatic patients with refractory ascites or unresponsive to diuretics.

- Patients with severe portal hypertension or refractory ascites may be referred for a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) insertion.

- A recent meta-analysis demonstrated lower rates of post-operative ascites in cirrhotic patients who received a TIPS insertion prior to surgery (OR=0.4). However, TIPS insertion did not decrease rates of 90-day mortality, perioperative transfusion requirements or postoperative hepatic encephalopathy.

- Therapeutic Paracentesis

- Symptomatic patients with severe and/or refractory ascites may particularly benefit from the procedure.

- A prospective, randomized study demonstrated increased success rates of paracentesis among emergency physicians using U/S guidance, as opposed to the traditional landmark technique (95% vs 61%).

- When To Refer to Interventional Radiology (IR)

- Consider referring to radiology if: you do not feel adequately prepared, there are anatomical complications (distended bladder/bowels, pregnancy), and/or the patient is not severely symptomatic.

- Relative Contraindications

- Pregnancy (U/S guidance indicated)

- Severe bowel distention (U/S guidance indicated)

- Bladder distention (empty before procedure and U/S guidance indicated)

- Evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or fibrinolysis (prophylactic preprocedural platelets and/or fresh frozen plasma indicated)

- Note: Most cases of ascites are due to liver cirrhosis and coagulopathies (ex. elevated INR, thrombocytopenia) are frequently concomitant. The rate of major bleeding complications in these patients following paracentesis is exceptionally low. Neither elevated INR, nor decreased platelets, have been shown to correlate well with bleeding risk. Prophylactic preprocedural platelets and/or fresh frozen plasma should be administered only in patients showing evidence of DIC or fibrinolysis.

- Albumin Replacement

- Large volume paracentesis (LVP) > 5L without adjunctive treatment is associated with post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction (PCD) and hyponatremia.

- The pathophysiology of PCD: decompression of splanchnic vascular bed → splanchnic vasodilation → activation of neurohormonal and RAAS systems → rapid water and sodium retention → renal failure, encephalopathy, refractory ascites and/or hyponatremia.

- If >5 L of ascitic fluid is removed, suggest replacing 6-8g of albumin 25% IV per liter of fluid.

- A retrospective review found no difference in adverse effects if fixed doses of albumin were given as follows: 25g for 5-6L, 50g for 7-10L and 75g for >10L of fluid removed.

- A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed an increase in PCD and hyponatremia in patients undergoing LVP without albumin replacement, but found that albumin replacement did not decrease rates of mortality, hospital readmission or severe complications.

- Sodium Reduction

- Patients should be advised to limit sodium intake to 2000mg/day.

- Diuretics

- Spironolactone and furosemide are the main diuretics used to treat ascites.

- Routine monitoring of blood pressure, fluid status, electrolytes and renal function is recommended to prevent iatrogenic hepatorenal syndrome due to overly aggressive diuresis.

- RCTs provide conflicting evidence regarding whether spironolactone monotherapy or spironolactone/furosemide combination therapy is more effective.

- Guidelines suggest the following:

- Spironolactone Monotherapy

- Recommended in first presentation or moderate ascites.

- 100mg/day, up to 400mg/day.

- Combination Therapy

- Recommended in persistent or severe ascites.

- Spironolactone 100mg/day, up to 400mg/day, AND

- Furosemide 40mg/day, up to 100mg/day.

- Spironolactone Monotherapy

Criteria For Hospital Admission

- SBP

- Variceal bleeding

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Severe decompensated liver disease

Criteria For Transfer To Another Facility

Lack of ability/resources to manage severe complications (SBP, variceal bleeding, HE).

Criteria For Close Observation And/or Consult

- Ascitic patients without severe complications may be monitored for improvement before discharge.

- Patients undergoing diuresis should be closely monitored for signs of over-diuresis.

Criteria For Safe Discharge Home

Asymptomatic patients with recurrent ascites of known etiology, and who lack severe complications, may be discharged home once their condition improves.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Higher success rates in ultrasound-guided paracenteses compared to landmark technique — Moderate — Validated in multiple smaller prospective trials.

LVP increases risk of PCD and hyponatremia but does not decrease mortality — Moderate — Validated in a single, large systematic review and meta-analysis.

No difference in adverse effects if albumin given in fixed interval doses following LVP — Low — Validated in a single, small retrospective trial.

Related Information

OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION

Paracentesis: https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/paracentesis/

Abdominal U/S Scan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4M_mon2ubH0

Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Summary:

https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/spontaneous-bacterial-peritonitis/

Pleural Effusion Summary: https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/pleural-effusion/

Upper GI Bleeding Summary:

Hepatic Encephalopathy Summary:

https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/hepatic-encephalopathy-diagnosis-management/

Reference List

Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, China L, Harmala S, Macken L, Ryan JM et al. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2021;70(1):9-29. Available from: https://gut.bmj.com/content/70/1/9.info

Rudralingam V, Footitt C, Layton B. Ascites matters. Ultrasound. 2017;25(2):69-79. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1742271X16680653

Cattau Jr EL, Benjamin SB, Knuff TE, Castell DO. The accuracy of the physical examination in the diagnosis of suspected ascites. JAMA. 1982;247(8):1164-1166. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/368603

Noone TC, Semelka RC, Chaney DM, Reinhold C. Abdominal imaging studies: comparison of diagnostic accuracies resulting from ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in the same individual. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22(1):19-24. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0730725X0300287X?via%3Dihub

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Mar 30, 2024

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.