Cocaine Toxicity

Cardiovascular, Critical Care / Resuscitation, Environmental Injuries / Exposures, Neurological, Pregnancy, Psychiatric and Behaviour, Toxicology

First 5 Minutes

High mortality rate with cocaine associated:

- Hyperthermia (worsening) portends imminent arrest: aggressive external cooling, sedation, and, if needed, intubation, to facilitate more invasive cooling measures.

- Delirium “Hyperactive delirium with severe agitation”.

– aggression, hyperactivity, extreme paranoia, hyperthermia, incoherent screaming, and excessive strength – needs aggressive sedation – restrain carefully supine/on side NOT face down (prone).

Other significant presentations – dysrhythmias, chest pain, headache/focal neurodeficit,

Consider mixed substances, either intentionally or unintentionally.

- E.g., IV heroin and cocaine = “speedballing” with initial signs of opioid toxicity but following the administration of naloxone, manifests signs of cocaine toxicity.

- Consider adulterants or “cutting agents”: caffeine, diltiazem, hydroxyzine, levamisole (agranulocytosis, vasculititis), Phenacetin.

Consider body packing or body stuffer when appropriate.

IF ANY CONCERN Call BC Drug and Poison Information Centre (BC DPIC)

24-Hour Line: 1-800-567-8911 or 604-682-5050.

(Telephone interpreting in over 150 languages available).

Context

- Cocaine – derived from cocoa leaves; Crack cocaine (also called free base) is alkalinized cocaine and is heat stable and can be smoked unlike cocaine.

- Presentation varies based on individual tolerance and dose.

- Multiple mechanisms of toxicity:

- Acute: blocks norepinephrine reuptake (adrenergic effects); blocks sodium/potassium channels (local anesthetic affects); and direct vessel damage.

- Chronic: cardiac fibrosis, myocarditis, and necrosis.

Diagnostic Process

Sympathomimetic Toxidrome:

- Diaphoretic

- Mydriasis

- Tachycardic

- Hypertensive

- Tachypneic

- Hyperthermic

- Agitated, psychosis, can hallucinate and,

- Seizures à focal – suspect intracerebral hemorrhage or infarction.

Common complications:

- Tachydysrhythmia – sinus tach; atrial fib; Torsade de Pointes, Ventricular tachycardia

- Severe hypertension

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Stroke

- Acute heart failure

- Acute renal failure

- Seizure

- Hyperthermia

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Neuropsychiatric: agitation, paranoia, mania, and severe delirium.

Uncommon complications:

- Paralysis from cocaine-associated vasospasm of an anterior spinal artery.

- “Crack lung” = fever, hemoptysis, hypoxia, ARDS, respiratory failure.

- Limb ischemia.

- Decreased LOC = intracerebral bleed/ischemia or co-ingestant of sedating drugs.

Investigations based on presentation:

- CBC, lytes, BS, BUN, Cr, LFT

- Troponin

- CK

- ECG

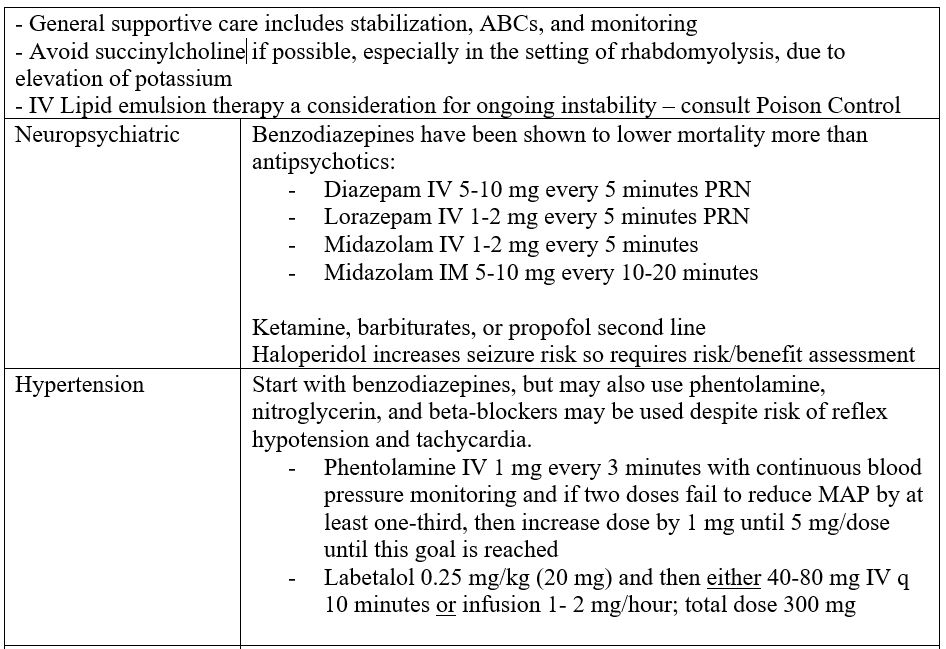

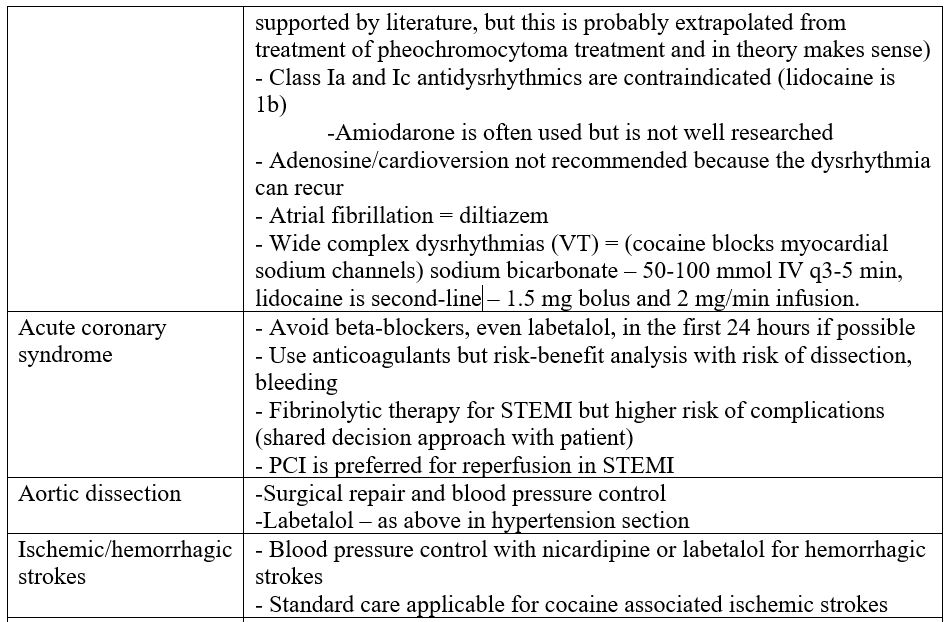

Recommended Treatment

- Non-pharmacological, including surgical treatments.

- Preferred or recommended drugs and dosages.

- Treatments to avoid (i.e., often used but shown to be ineffective).

Criteria For Hospital Admission

- The following are considerations to admit if not resolving:

- Hyperthermia.

- Rhabdomyolysis.

- Other signs of end-organ damage.

- Diagnostic or evolving ECGs suggesting ischemia or infarction.

- Dysrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia.

- Positive cardiac biomarkers and ongoing symptoms.

- Congestive heart failure.

- Passage/monitoring of patients presenting with body packing.

- Keep low threshold for pediatric patients even if sympathetic toxicity symptoms are mild.

Criteria For Close Observation And/or Consult

- Contaminants change rapidly and vary by geographic region.

- If the patient presentation is confusing, call poison control center.

- If hypotension and QRS prolongation do not improve with sodium bicarbonate, consider intravenous lipid emulsion therapy with a medical toxicologist.

- Consult surgery for body packers with symptomatic patients.

- Consult obstetrics if an obstetric patient is found as developmental abnormalities of fetus/neonate may occur.

– Counselling and substance use support.

Criteria For Safe Discharge Home

- Considerations for safe discharge

- Patients with relatively mild sympathomimetic presentation that resolve spontaneously.

- Patients who show no signs of end-organ damage.

- Patients with no concerning history or presentation elements.

- Patients with good response to sedation therapy.

- Discharge after vital signs and mental status remain normal after 4-6 hours.

- Body packers need to have passed all packets and remain asymptomatic with normal vitals for 6-12 hours.

- For patients with chest pain

- Some centers recommend up to 12 hours of monitoring but more are moving to shorter durations.

- Application of an abbreviated cardiac enzyme protocol (at 0, 2, 4, and 8 hours) with continuous cardiac monitoring can be considered.

- Patients who are pain free with no abnormalities on ECG can be discharged if a single cardiac marker after 8 hours of the onset of chest pain is normal.

- For all patients, provide a referral for detoxification.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

The mainstays of treatment of sedation and cooling of body temperature have been shown to be of benefit. The treatments of complications and second-line treatments, however, are derived from a lower quality of evidence.

Related Information

Reference List

Lewis SN, Mary AH, Neal AL, et al. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 11th edition. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

Chary MA, Erickson TB. Cocaine and Other Sympathomimetics in Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 10th edition. Elsevier; 2023.

Zimmerman LJ. Cocaine Intoxication. Critical Care Clinics; 2012.

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Aug 20, 2024

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.