Pain Management in the ED (Diagnosis and Treatment)

Cardinal Presentations / Presenting Problems

Context

Pain is the leading complaint that motivates patients to present to the emergency department (ED(1,2). Physicians should be able to adequately manage and optimize the patient’s pain during their time in the ED(1). In emergent situations, pain relief can also have physiological advantages such as in acute coronary syndrome or in patients with elevated intracranial pressure(1).

Clinical indicators of pain(1,3,4)

Numerical rating scale (NRS) – rate pain numerically on a scale from 0 to 10.

Visual analog scale (VAS) – line drawn between end point descriptors ‘no pain’ on one side and ‘worst pain imaginable’ on the other end. Patient marks a point on the line to represent their pain.

Brief pain inventory (BPI) – self-administered questionnaire to assess severity and impact of pain on function.

Management

Non-pharmacological management

Non-pharmacological methods should not be overlooked in the management of acute pain.

- Relaxation techniques – stress and tension reduction through breathing exercises, mental imagery, music, and meditation.

- Cognitive behavioural therapy.

- Cold and heat application.

- Fracture stabilization and bracing.

- Patient positioning.

- Physiotherapy.

Pharmacological management

An initial trial of non-opioid analgesics using a multimodal approach should be used, targeting various receptors and mechanisms of action(5). Opioids have a role in managing severe and acute pain in the emergency department(6,7). The use of opioids warrants careful consideration given the potential for opioid abuse(6,7).

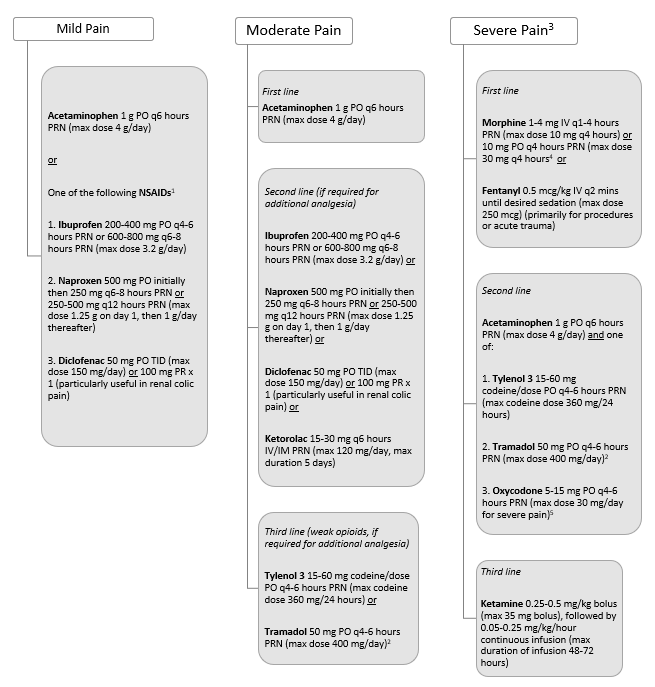

Adults(8)

1Use with caution in elderly and avoid NSAIDs during pregnancy (if essential, use during the second trimester only), PUD and asthmatics with a history of worsening bronchospasm with NSAIDs.

2Use for ≤3 days is often sufficient to provide adequate analgesia, use >7 days is rarely required.

3Consider acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs PO as per recommendations for moderate pain.

4If patient is on chronic opioid therapy for pain, morphine 5-20% of basal daily morphine milligram equivalents can be given using an immediate release formulation PO, IV, SC.

5If patient is on chronic opioid therapy for pain, oxycodone 5-15% of basal daily oxycodone requirement can be given using an immediate release formulation PO, IV, SC q4-6 hours PRN.

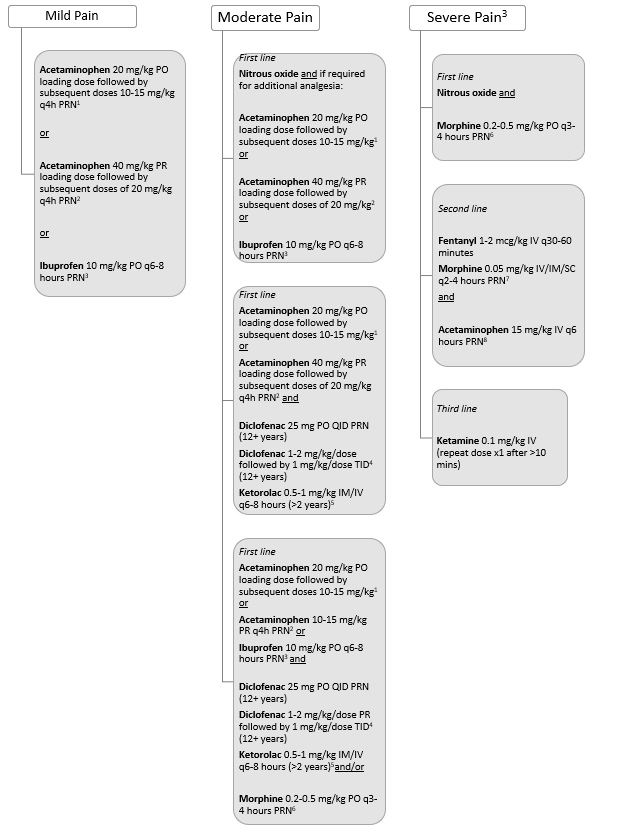

Children up to 12 years old(8)

1Max dose acetaminophen PO is 75 mg/kg/day (max of 5 daily doses), not to exceed 4000 mg/day.

2Max dose acetaminophen PR is 75 mg/kg/day (max of 5 daily doses), not to exceed 1625 mg/day.

3Max dose of ibuprofen PO is 40 mg/kg/day or 3200 mg/day (whichever is less).

4Max dose diclofenac PR is 3 mg/kg/day, max single dose 50 mg/dose, not to exceed 4 days of treatment.

5Max dose ketorolac IV/IM is 30 mg/dose, usually duration 48-72 hours, not to exceed 5 days of treatment.

6Max dose of initial morphine PO is 15-20 mg.

7Max dose or morphine IV/IM/SC is 1-2 mg/dose.

8Max daily dose acetaminophen IV is 60 mg/kg day.

Effectiveness of analgesia

Adequate analgesia can be defined as a reduction in pain score of 2+ points and to a level <4 on a pain scale from 0-10(9). This definition was significantly associated with improved patient satisfaction with pain management in the ED(9).

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Optimize non-opioid pharmacotherapy and nonpharmacologic therapy prior to a trial of opioids.

Recommendation against opioids in patients with chronic, non-cancer pain and active substance use disorder.

For chronic noncancer pain starting opioid therapy, the recommendation is to restrict the prescribed dose to less than 90 mg morphine equivalents daily.

A formal multidisciplinary team is recommended for patients with chronic noncancer pain who are having troubles tapering their opioid dose.

Recommendation for a trial of opioid therapy in patients with chronic noncancer pain refractory to nonopioid analgesia and without a history of or current substance use disorder.

Recommendation against opioids in patients with chronic, non-cancer pain and a history of substance use disorder.

Recommended to stabilize any active psychiatric conditions prior to a trial of opioid therapy for persistent chronic noncancer pain.

For chronic noncancer pain patients who are using 90 mg morphine equivalents of opioids per day, it is suggested to taper to the lowest effective dose and potentially discontinuing the therapy.

For chronic noncancer pain starting opioid therapy, the recommendation is to restrict the prescribed dose to less than 50 mg morphine equivalents daily.

For chronic noncancer pain in patients on opioid therapy currently, it is suggested to trial alternative opioids rather than continuing with the same opioid.

Related Information

Reference List

Sahu S. What’s new in Emergencies Trauma And Shock – Adequate Pain Management in the Emergency Department – A Dream Come True!. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2017;10(4):167-168. doi:10.4103/JETS.JETS_64_17.

Chang H-Y, Daubresse M, Kruszewski SP, et al. Prevalence and treatment of pain in EDS in the United States, 2000 to 2010. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:421–31.doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.015.

Mohan H, Ryan J, Whelan B, Wakai A. The end of the line? The visual analogue scale and verbal numerical rating scale as pain assessment tools in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(5). 372-375. https://emj.bmj.com/content/27/5/372

Im DD, Jambaulikar GD, Kikut A, Gale J, Weiner SG. Brief pain inventory – short form: a new method for assessing pain in the emergency department. Pain Med. 2020; 21(12): 3263-3269. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa269

Duncan RW, Smith KL, Maguire M, Stader DE. Alternatives to opioids for pain management in the emergency department decreases opioid usage and maintains patient satisfaction. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2019;37(1):38-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.04.043. Accessed Jan 15, 2022.

Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661–1667. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16190.

Ducharme J. Acute Pain Management. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, et al., eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://doi.org/accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1166529275

Hachimi-Idrissi S, Dobias V, Hautz WE, Leach R, Sauter TC, Sforzi I, Coffey F. Approaching acute pain in emergency settings; European Society for Emergency Medicine (EUSEM) guidelines—part 2: management and recommendations. Intern Emerg Med. Sept 2020; 15: 1141-1155. Accessed Jan 25, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02411-2

Jao K, McD Taylor D, Taylor SE, Khan M, and Chae J. Simple clinical targets associated with a high level of patient satisfaction with their pain management. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2011; 23: 195-201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01397.x

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley N, Wang L, Couban RJ, Agoritsas T, Akl EA, Carrasco-Labra A, Cooper L, Cull C, da Costa BR, Frank JW, Grant G, Iorio A, Persaud N, Stern S, Tugwell P, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Can Med Assoc J. May 2017; 189(18): E659-E666. Accessed Jan 25, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170363

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Feb 17, 2022

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.