Geriatric Pain Management in the Emergency Department

Cardinal Presentations / Presenting Problems, Special Populations

Context

- Elderly patients account for 25% of Canadian emergency department (ED) visits and acute pain is one of the leading complaints.

- Studies have shown that geriatric patients with pain-related complaints are less likely to receive analgesics compared to young adults leading to inappropriate/insufficient pain management.

- Barriers to optimal analgesia include under recognition, sub-optimal evaluation (delays in pain assessment and management, challenges in conducting a thorough history and physical), and unconscious bias by healthcare professionals.

- Poor pain management in older adults is associated with worse outcomes including longer length of stay, delays to ambulation, a greater incidence of delirium, subsequent functional decline and behavioural issues such as agitation, aggression, wandering and refusal of care.

- A recent study has shown that untreated pain is more strongly associated with the development of delirium than opioids in older adult patients in the ED, thereby highlighting the importance of appropriate pain control in this patient population.

- The classic approach to diagnosis and treatment can be difficult to implement in this patient population due to vague symptoms, cognitive or physical impairments, and predisposition to adverse drug reactions from altered pharmacokinetics.

Diagnostic Process

According to the American College of Emergency Physicians and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine:

- Formal assessment for the presence of acute pain should be documented within 1 hour of patient arrival in the emergency department.

- A second pain assessment should be documented if the patient remains in the emergency department for more than 6 hours.

Pain assessment tools:

Recommended Treatment

Goals of geriatric pain management in the ED:

- Use of a multi-modal analgesic strategy (pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches).

- Early initial assessment of pain followed by frequent reassessment (within 15-20 min if administering IV opioids and within 20-30 min if administering oral analgesics).

- To reach an acceptable level of pain for function (the goal is not zero pain).

- Balance pain relief and risk of unwanted side effects.

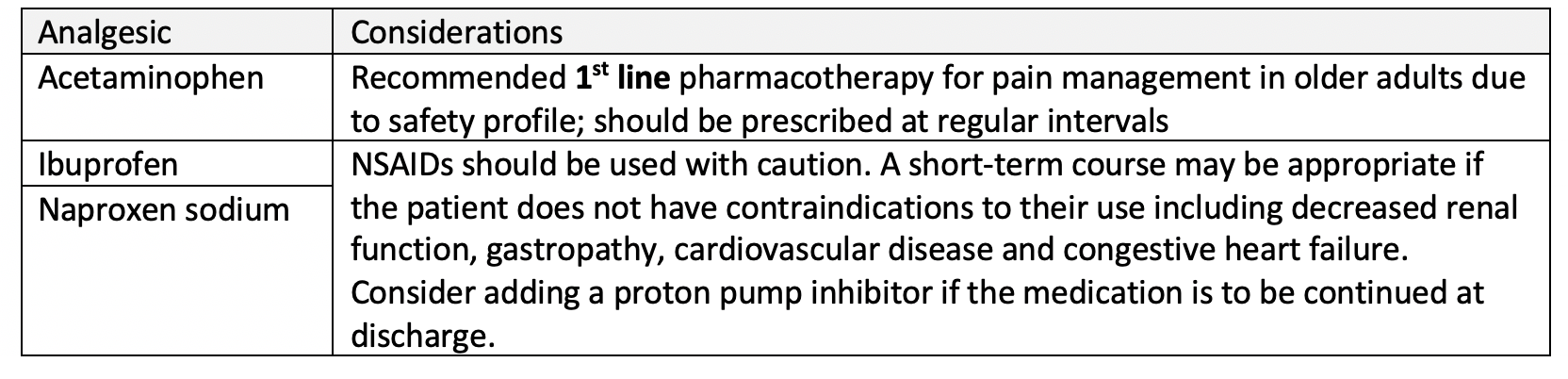

Non-opioids – recommended for mild ongoing and persistent pain.

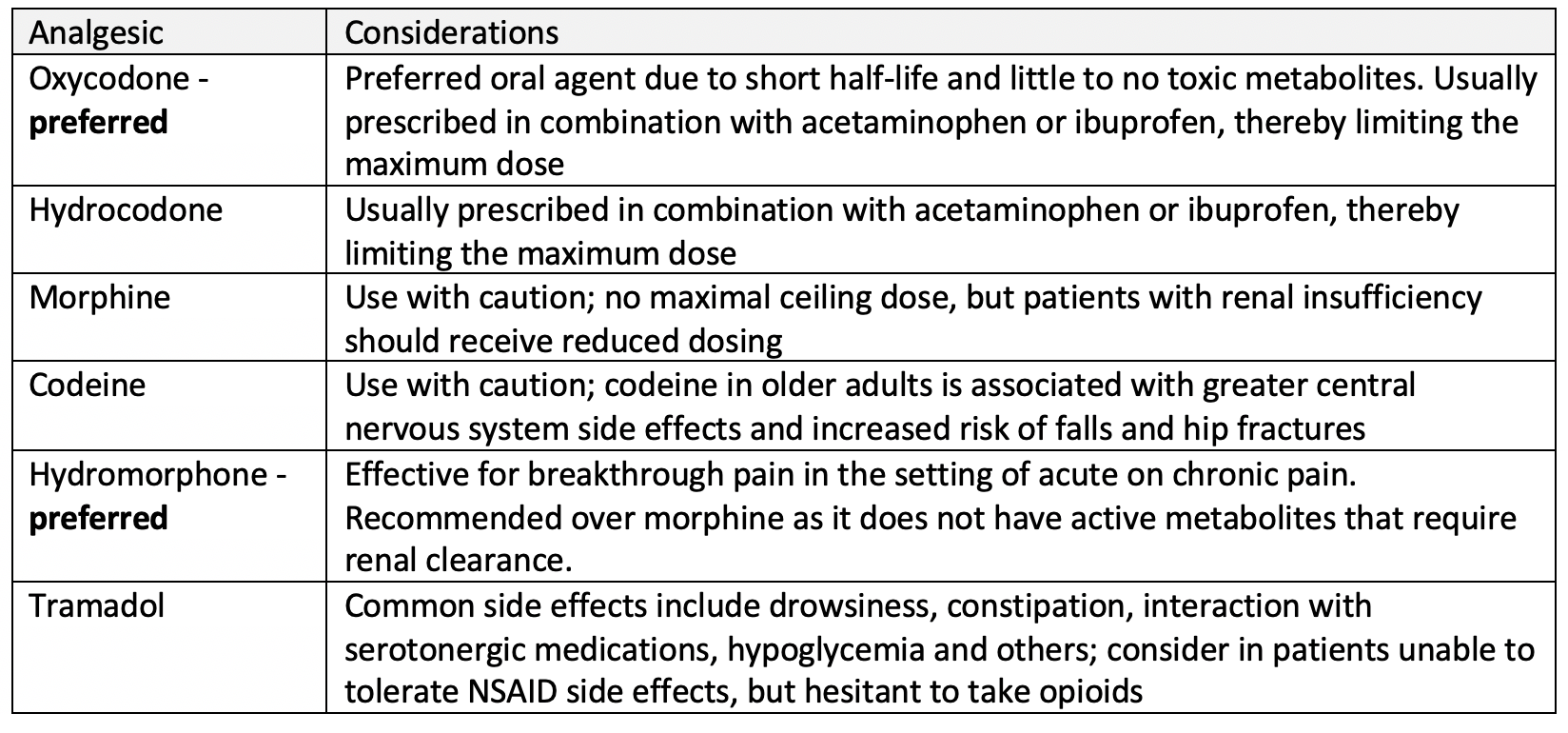

Opioids – recommended for moderate to severe pain.

- Doses of opioids should be reduced by 25-50% (start low and go slow), with the exception that patients with a history of chronic opioid consumption will likely need higher starting doses for optimal pain control.

- Patients should be monitored vigilantly for respiratory depression and other side effects of opioid therapy including nausea/vomiting, dizziness, constipation and somnolence.

- Bowel regimen should be provided if the opioid analgesics are to be continued upon discharge.

Non-pharmacologic options for use in older adults:

- Optimize local analgesics whenever appropriate; for example, femoral nerve blocks for pain due to hip fracture.

- Alternate non-pharmacologic therapies such as positioning, heat and cold have not been studied in the ED setting for their feasibility and effectiveness.

Drugs to avoid:

- Meperidine (Demerol) should be avoided in older patients because it accumulates with renal impairment and has neurotoxic effects.

- Ketorolac should be avoided due to its higher risk for gastric ulcers.

- Refer to the Beers criteria for a list of inappropriate medications to use in older adults.

- The STOPP criteria is another validated screening tool for potentially inappropriate prescriptions in older adults that can be used to determine if certain medications are suitable in this patient population and/or guide medication prescribing on discharge.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

While there are multiple tools available to assess pain in older adults, they have not been validated specifically for the emergency setting and no single study has identified a superior tool. Furthermore, there is a paucity of guidelines for acute analgesic treatment in older adults.

Related Information

OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION

Image of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale.

Image of the analgesic pyramid stratifying agents by pain severity.

Video: Beyond the Geriatrogram – Frailty, Falls and Pain in the Older ED Patient.

Recommended CPD course for topic: Geriatric EM.

Reference List

Walls R., Hockerberger R., & Gausche-Hill M. (eds) Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

Daoust R., Paquet J., Boucher V., Pelletier M., Gouin É. & Émond M. (2020). Relationship between pain, opioid treatment, and delirium in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 27(8):708–16. DOI: 1111/acem.14033.

Hwang U. & Platts-Mills T.F. (2013). Acute pain management in older adults in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 29(1):151–64.

Benhamed A., Boucher V. & Emond M. (2022). Pain management in emergency department older adults with pelvic fracture: still insufficient. CJEM. 24:245-246. DOI: 1007/s43678-022-00299-9.

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Aug 17, 2022

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.