Real-Time Virtual Support: What EM Practitioners Want

Findings From Emergency Practitioners

On September 27, 2019, a group of emergency medicine practitioners met for a workshop on real-time virtual support for emergency care. Key findings from this discussion are summarized below, augmented by data collected from a physician survey on real-time virtual support.

The purpose of the workshop was to share the BC virtual health landscape and to incorporate the wisdom of future users. Nearly 50 rural and urban practitioners attended. Dr. Kendall Ho, an emergency medicine physician at VGH and leader of the UBC Digital Emergency Medicine Research Group, facilitated the talk.

Insights on Virtual Support

Prior to the group discussion, four physicians from across BC shared their insights on real-time virtual support for emergency care.

Broad, Systemic Support

Dr. Jim Christenson, an emergency physician at St. Paul’s Hospital, Head of UBC Department of Emergency Medicine, and Executive Lead of the BC Emergency Medicine Network, spoke about the EM Network real-time support mandate. He explained, “Emergency Medicine Real-time Virtual Support will provide on-demand consultation to help care for your patients.” The Ministry of Health has recognized the importance of supporting virtual care and its value to rural communities, said Dr. Christenson.

Emergency Medicine Real-time Virtual Support will provide on-demand consultation to help care for your patients

Regional Equity

Dr. John Pawlovich, a rural family physician and a pioneer in BC virtual care, highlighted the importance of regional equity. An underlying theme of virtual care is to ensure health equity for everyone regardless of their geographic location.

Fee Codes

Dr. Gord McInnes, co-president of Doctors of BC Section of Emergency Medicine and an emergency physician in Kelowna, provided insight into the daunting role of fee codes in emergency medicine. He highlighted that some rural GPs providing emergency care might feel unsupported by the Doctors of BC Section of Emergency Medicine. The government is supportive of virtual care, but there is a need to improve the billing process in order to implement the change.

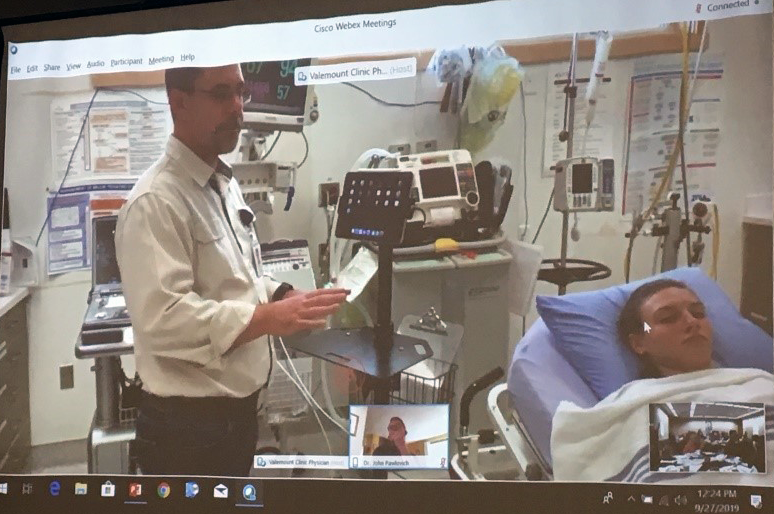

Live CODI Demo

Dr. Stefan du Toit, a family physician from Valemount, BC, demonstrated a real-time support call. Audience members witnessed the call from the perspective of a rural physician via teleconference. Dr. du Toit used a mobile cart for an iPad for hands-free functionality, and an app called CODI. CODI enables a one-touch connection with an on-call intensivist for patient consultation. The call demonstrated how real-time virtual care provides a better link between rural and urban settings and can facilitate mutual learning.

Insights from Future Users

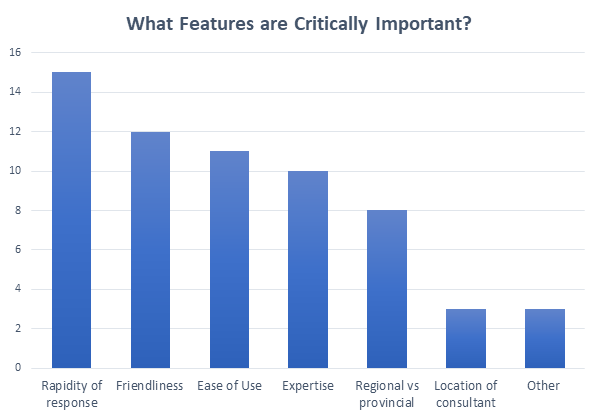

Physicians attending this discussion overwhelmingly agreed there is a need for real-time virtual support for BC practitioners practicing emergency medicine. Participants identified several features critically important for a real-time virtual health service, summarized in Figure 1.

Several of these features were topics of discussion for three questions proposed to the group.

Figure 1. Essential features for EM real-time virtual health service. (Selected by survey respondents.)

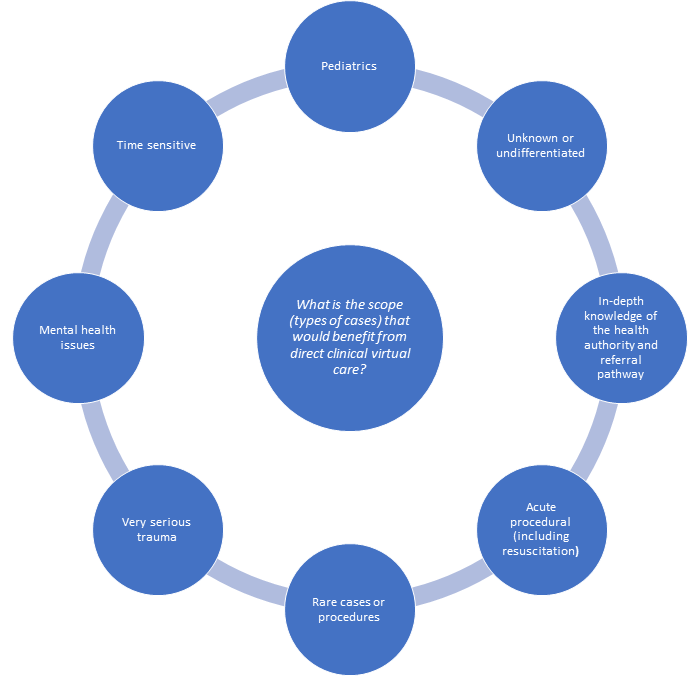

Question 1: What is the scope (types of cases) that would benefit from EM virtual care?

The group discussed a broad spectrum of cases not commonly seen by rural physicians (Figure 2). Dr. Pawlovich recognized that rural generalism necessitates broad-based support because rural GPs are responsible for emergency care, obstetrics, and more. Rural physicians don’t have the luxury of having a colleague “to float it by.” For example, for a case of undifferentiated abdominal pain, getting a second opinion is often useful.

Virtual care is also useful for cases that you “don’t know whether you should be worried or not,” including unknown, undifferentiated, or pediatric cases. Many survey respondents also echoed that virtual support would be most useful for unknown, unclear, or still pending diagnosis patients.

Some emergency cases are challenging to manage because they don’t often occur in a rural setting. In those cases, it’s helpful to have “over the shoulder advice” via virtual care to reduce stress and tunnel vision.

Additionally, some cases require distinction because they are overlapping. These cases include acute procedural or resuscitation cases, and when an in-depth knowledge of the health authority, referral pathway, and transportation service is needed.

Figure 2. Types of cases and scope that would benefit from EM virtual care, identified in workshop discussion.

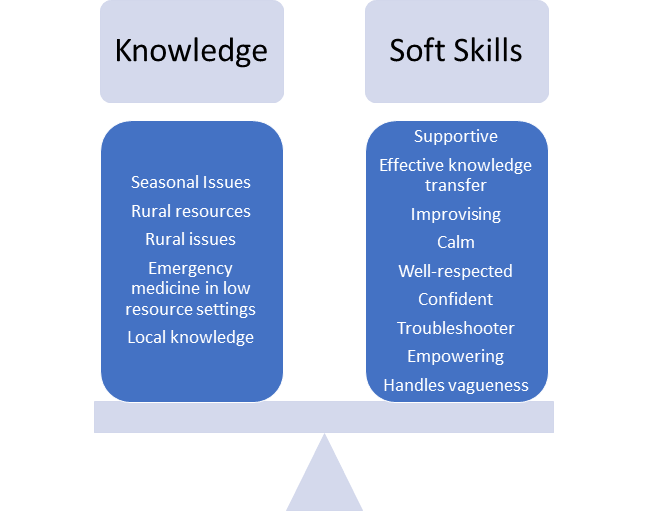

Question 2: What are the ideal characteristics of a consultant?

Knowledge and Location

While being knowledgeable about the rural context is essential, only a small number of survey respondents thought the location of the consultant was important (Figure 1).

Soft Skills

A central topic of discussion was that a consultant’s practical knowledge is not enough. A consultant must have the soft skills necessary to interact with a rural physician – understanding and empathizing with their context (Figure 3). A counterexample to these soft skills is the small percentage of consultants who may respond with “I can’t see the patient, I’m not there.” Or getting pushback when calling after 10 pm, when you may need help the most. A large percentage of survey respondents valued friendliness as a crucial characteristic for real-time virtual support consultant.

Table 1. Ideal characteristics for a virtual support consultant, identified in workshop discussion.

Question 3: What’s the right model for coverage and availability/workflow?

Figure 4, below, highlights areas proposed for a real-time virtual emergency care model. Discussion participants suggested using a regional model of virtual consultants who are aware of referral and resource patterns. However, survey responses differed on whether to use a local versus provincial model (Figure 1).

An alternate model raised during the discussion was to have a regional consultant in 3-4 sites across the province, allowing for local and broad knowledge. Creating a group comprised of people with interest and aptitude would be more effective than creating a group arbitrarily or using an existing group.

Incorporating the Patient Transfer Network (PTN) would improve efficiency for patients that require a transfer. Participants suggested that lower volume pediatrics cases should be a separate category in this model.

Figure 4. A model for virtual support coverage, identified in workshop discussion.

Get Involved

Through this discussion, physicians expressed their voice regarding the necessity of real-time virtual care. Key finding: real-time virtual consultants must have the necessary knowledge and soft skills to provide support for complex and rare cases. The next step is forming a working model for real-time virtual care, including consultants with the aptitude and interest.

We want to hear your thoughts on real-time virtual health in BC: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/SLTWN66.

Your feedback will shape the future of real-time virtual health in BC. For more information, or to join the EM Network Real-Time Support Working Group, please email Dr. Kendall Ho at kendall.ho@ubc.ca.

This workshop was held at the St. Paul’s Emergency Medicine Update Conference. It was sponsored and supported by the BC Emergency Medicine Network and BC Academic Health Sciences Network.

The authors thank the BC Emergency Medicine Network, Rural Coordination Centre of BC, Doctors of BC, Rural Education Action Plan, Section of Emergency Medicine, UBC Department of Emergency Medicine, Northern Interior Rural Division of Family Practice, and BC Academic Health Science Network for their participation and support. Thanks also to St. Paul’s Emergency Medicine Update for providing the space and time at their conference in Whistler, BC.