Rashes in Pregnancy – Diagnosis and Treatment

Cardinal Presentations / Presenting Problems, Inflammatory, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Context

- The immune system undergoes dynamic change in pregnancy, which can result in inflammatory/autoimmune processes that manifest in the skin as a rash.

- There are 5 main pathological dermatoses exclusive to pregnancy, 3 of which are associated with fetal morbidity and thus important to recognize.

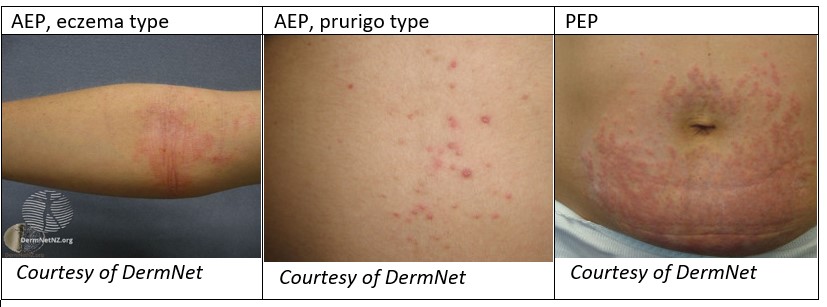

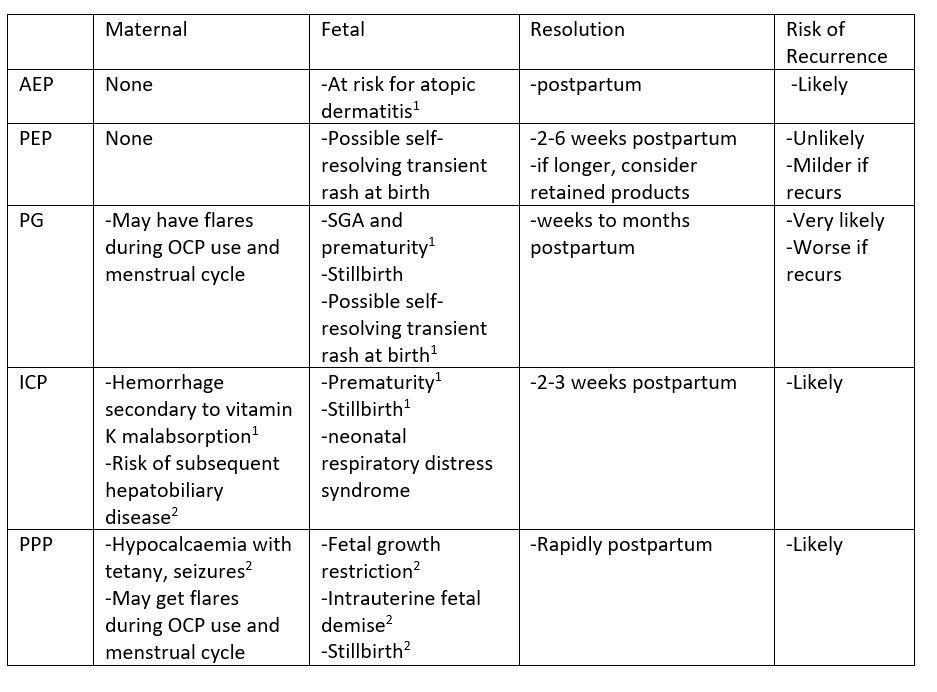

- Atopic Eruption of Pregnancy (AEP) is the most common and often associated with those predisposed to atopy. There are 3 phenotypes within this category: eczema-type, prurigo-type, pustular folliculitis-type. It is benign to the fetus1.

- Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy (PEP) (previously PUPPP) is thought to be an autoimmune response to damaged connective tissue generated in abdominal striae, thus more common with rapid weight gain or multiple gestations. It is benign to the fetus1.

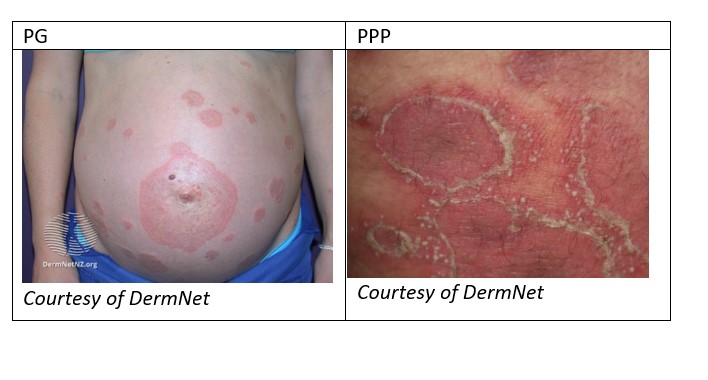

- Pemphigoid Gestationis (PG) is a rare condition where IgG act against a collagen subtype. This collagen is found in the cutaneous basement membrane, leading to bullous formation. It is also found in placental tissue, leading to fetal risk1.

- Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (ICP) is a reversible cholestasis of unclear etiology thought to be triggered by hormonal changes in pregnancy. The increase in serum bile acid is fetotoxic and associated with significant fetal morbidity1.

- Pruritic Psoriasis of Pregnancy (PPP) is a rare variant of general pustular psoriasis exclusive to pregnancy and of unknown etiology. Although rare, it carries a poor fetal prognosis if not treated promptly.

Diagnostic Process

History and Physical

- Determine gestational age of pregnancy, ensure presence of fetal movements.

- Gather prenatal history, including rashes in prior pregnancies.

- Personal or family history of atopy is common in AEP.

- Ask about any recent drug, environmental or travel exposures as non-pregnancy related rashes are common.

- Large blisters raise suspicion for PG or PPP.

- Any umbilical involvement raises concern for PG.

- Pruritis with no primary lesions raises concern for ICP.

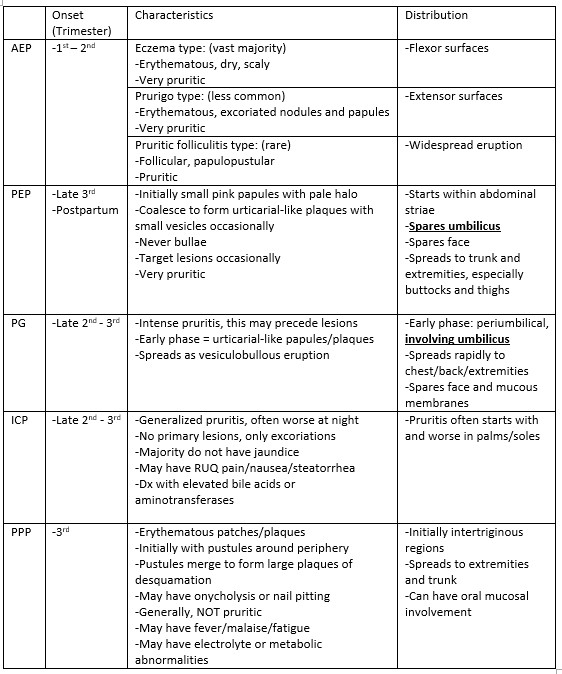

Benign Dermatoses of Pregnancy

Non-Benign Dermatoses of Pregnancy

Biopsy

- Biopsies should generally be undertaken in consultation with a dermatologist.

- Utility for confirming PG and PPP with histopathology and direct immunofluorescence.

- No diagnostic value for confirming AEP, PEP or ICP.

- Consider biopsy to rule out PG or PPP whenever there is clinical uncertainty. The early urticarial stage of PG can mimic PEP/AEP.

Labs

- Swab and culture any pustules to rule out infective etiology.

- Advisable to routinely order total serum bile acid concentration and serum aminotransferases (AST/ALT) to rule out ICP if there is an element of pruritis.

- If concern for PPP, order a CBC with differential, electrolytes, serum albumin, a liver panel, urea, and creatine, as these all may be involved.

Diagnostic considerations

- Pruritis can precede serum findings in ICP. If suspicious, weekly labs should be arranged through the primary care provider and an obstetrician should be involved.

- HELLP syndrome cannot be missed in the pregnant patient.

- Watch out for dermatoses indicative of TORCH infections as these are related to placental insufficiency, congenital infection, and fetal morbidity. These include: toxoplasmosis, rubella, CMV, HSV, VZV, HIV, Zika, HFM, syphilis.

- Pregnancy can cause some pre-existing dermatoses to improve and others to worsen.

- Be aware of normal skin changes in pregnancy including linea nigra, melasma, striae gravidarum and changes to melanocytic naevi.

- Always consider non-pregnancy related dermatoses in the pregnant patient.

Recommended Treatment

Treatment

AEP

- Goal = symptomatic relief.

- Treat like eczema with liberal emollient use, irritant avoidance and a low-mid potency topical corticosteroid until symptoms improve2.

PEP

- Goal = symptomatic relief.

- Treat with emollients and mid-high potency topical corticosteroids until symptoms improve1,2.

- Very severe or generalized cases may require a short course of systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisolone 40-60mg/day, tapering doses for a few days1,2).

PG

- Goal = reduce disease activity and relieve symptoms.

- Mild cases may respond to high potency topical corticosteroids1,2.

- Significant or generalized disease will likely require systemic corticosteroids (ex: prednisolone starting at 0.5-1mg/kg/day1,2) until symptoms stabilize. Taper to the lowest effective dose1.

- Obstetrics consult to manage fetal risk.

ICP

- Goal = reduce bile acid concentration to reduce fetal and maternal risk.

- Treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (off-label), 15mg/kg/day1,2.

- Bile acid and transaminases should be monitored moving forward due to dangerous toxicity to fetus.

- Obstetrics consult to manage fetal risk.

PPP

- Goal = prompt treatment to minimize fetal risk.

- Correct any electrolyte or metabolic abnormalities that are present.

- Initial recommended treatment = systemic corticosteroids (ex: high dose prednisolone, up to 60-80mg/day2) for 2-3 days before tapering to lowest effective dose.

- May require alternative immunosuppressant treatment.

- Obstetrics consult to manage fetal risk.

Complications

Disposition

- Obstetric referral is required for PG, ICP and PPP to manage fetal risks2. Further fetal monitoring may be required, and these diagnoses may change obstetrical management.

- ICP requires close obstetrical monitoring due to toxicity to fetus, and bile acid levels should be monitored as they may indicate early delivery2.

- Consider dermatology referral or consultation in cases of PG and PPP likely requiring systemic corticosteroid therapy to ensure adequate disease management.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Little clinical evidence exists regarding the management of PG and PPP due to their lack of prevalence, despite these being two of the concerning diagnoses.

Related Information

Reference List

Ambros-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy – clues to diagnosis, fetal risk and therapy. Ann Dermatol 2011; 23:265.

Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther 2013; 26:274.

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Feb 08, 2023

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.